Two Aerospace Engineering Students Help Analyze OSIRIS-REx Sample

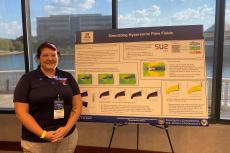

The world is waiting to learn what the asteroid sample returned by the OSIRIS-REx mission will reveal, and two aerospace engineering students are helping discover the answers. Maanyaa Kapur and Zach Purdie are NASA interns and members of the sample analysis team at the University of Arizona Lunar and Planetary Laboratory.

Kapur, who earned her bachelor’s at the UA and is completing a master’s, knew she wanted to work in aerospace since she first saw images of the Mars Curiosity Rover in 2012. She began her NASA internship in 2021. Purdie served in the U.S. Navy for five years, working as an avionics technician before beginning his studies. He began his internship a little over a year ago and is in the final year of undergraduate studies.

The opportunity to participate in a project as complex and sophisticated as OSIRIS-REx has provided them ample hands-on experience and a front-row seat on how a major mission is prepared and executed.

The OSIRIS-REx mission is important for two major reasons. First, it will give a window onto the formation of the solar system some 4.5 billion years ago. Scientists have already discovered evidence of carbon and water in the samples.

“If a small asteroid like Bennu hit the Earth, could it be what first delivered carbon and water to Earth?” asked Kapur. “If so, could such a strike have provided the building blocks for life on Earth?”

The mission could also yield information for planetary defense. “If we had to shoot down an asteroid headed for Earth at some point, you would want to know the physical qualities of the asteroid, how it would break apart and how the parts would behave,” Kapur said.

Varied, Valuable Experience

NASA’s OSIRIS-REx mission is led by the UA. The spacecraft was launched in 2016 and reached the 4.5-billion-year-old Bennu in 2018. After remaining in the asteroid’s vicinity for more than two years while scientists looked for an optimal point from which to take a sample, in October 2020, OSIRIS-REx approached Bennu and drove its robotic arm into Bennu’s surface to capture a sample and fired its thrusters to reverse the descent and separate from the asteroid. The craft went on to study another asteroid while the return capsule landed in the Utah desert on Sept. 24, full of a robust sample.

Scientists at the UA and elsewhere will study the Bennu sample for decades to learn more about the formation of the solar system. Under the tutelage of Andrew Ryan, a research scientist at the LPL, Purdie and Kapur were part of a team that designed and developed an apparatus to assess the thermal conductivity of the sample. Knowing how well the asteroid conducts heat will help researchers identify the make-up of the asteroid.

One of Purdie’s tasks has been to create a sample standard, a mock-up of an actual asteroid sample, using metallic 3D printing. “We volumetrically scan the sample and create an analogous version in stainless steel, which has a known thermal conductivity, to create a control or calibration standard for measuring the sample itself,” he explained.

In addition, Purdie has been integrally involved in everything from wiring up the instruments to software design.

The process of creating the experiment and building the apparatus and data collection system was eye-opening for Purdie. “The thing that kind of stuck out was the crossover between different fields. You work on a space mission like this, and you really get to see all the different types of engineers it takes to do even one project and get the end result,” he said. “Being able to dip my toes into each aspect of this project, and see how things are applied, has been very beneficial, as opposed to just getting aerospace knowledge from classes.”

“You have to prepare the software so it’s conducive to reading the data in a way that makes sense, of course, but also transferring it to a platform where it can be plotted for use by Dr. Ryan,” he said.

Kapur’s experience has been similarly varied.

“I’ve worked on the propulsion side of things, the aerodynamic side, and now the mechanical design component with the mission,” she said. “I’m fortunate in having a lot of different research tracks.”

Kapur also worked closely with the aerospace and machining shop to fine-tune the hardware for the testing apparatus.

“I went from being a student to creating a mechanical design with SolidWorks software, and then working with the machinists to get these very fine levels of precision, even down to which machines to use for the best fabrication. I feel like I grew so much within this role in the last two years because of the work environment that was there.”

After earning her master’s degree, Kapur has her eyes set on industry, and she is finding that potential firms have noticed the variety and pragmatic aspects of her work and research at the university.

“Designing an experimental setup on my computer, getting it fabricated and assembled, and then putting it inside a vacuum chamber was an amazing learning experience, and people in industry seem to appreciate that,” she said.

Purdie is still weighing his post-graduation options. Industry is a possible track, but he’s also intrigued by graduate programs focusing on mining in space, like the Colorado School of Mines Space Resources program.

“I told them about my work with OSIRIS-REx, and they seemed impressed,” he said. “It directly correlates to their program, and it would mesh my interests in aerospace and materials science.”