Researchers take power and efficiency of biological sensing to record level

Latest FLOWER device application could lead to better health outcomes and diagnostics.

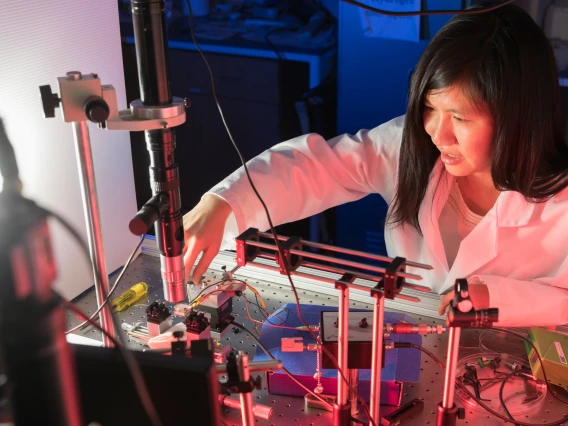

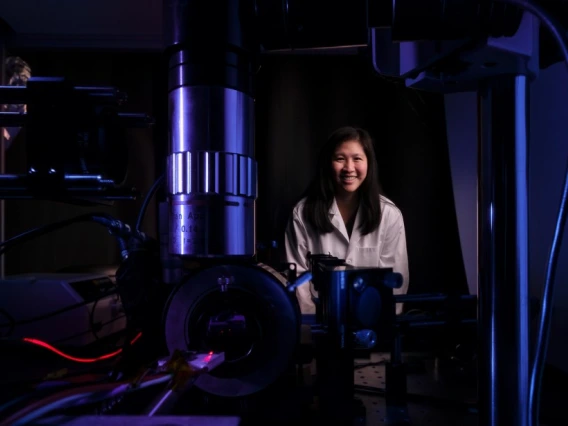

In the University of Arizona’s Little Sensor Lab, Judith Su and collaborators use ultrasensitive optical sensing for a wide variety of applications.

University of Arizona researchers have developed a new biological sensing method that can detect substances at the zeptomolar level, an astonishingly miniscule amount. This level of sensing, immediately useful for drug testing and other research, has the potential to make new drug discoveries possible. Eventually, the advance could lead to portable sensors that can detect environmental toxins or chemical weapons, monitor food quality, or screen for cancer. A paper laying out the results was published in Nature Communications Aug. 28. Judith Su, associate professor of biomedical engineering and optical sciences, led the research for the UA, collaborating with Stephen Liggett from the University of South Florida. Their method uses the FLOWER device, invented by Su, to pick up target compounds at zeptomolar (10-21) concentrations and without the current need for labeling – adding a fluorescent or radioactive tag to make a target compound stand out during testing.

Label-free optical tech

Detecting a particular target compound in an environment – or seeing if it reacts with a particular protein, for instance – is a tricky business. Su, principal investigator at the university's Little Sensor Lab and a Craig M. Berge Faculty Fellow, explained that one of the current hurdles to biosensing is that, in the most prevalent technologies, the sensing compounds must be labeled.

FLOWER, an acronym for frequency locked optical whispering evanescent resonator, is label-free. The sensing substances can be used in their native state to detect a target compound. “In certain applications, it can be really difficult or impossible to put these tags on, and they can increase cost. For things like small molecule drug screening, sometimes the tags can interfere with the results,” said Su, also an associate professor at the BIO5 Institute. FLOWER, which has also been used to detect diseases and toxic gases, uses optical technology. The core of the FLOWER tool is a microtoroid – a glass doughnut supported by a round pedestal. The microtoroid is coated with chemical compounds that capture the target biochemical agents. Its rim guides light in a fashion similar to an optical fiber. Light of a very specific wavelength will resonate when it passes through the microtoroid. As disease biomarkers or toxic gases get captured, the resonance wavelength shifts slightly. By comparing light that passes through the microtoroid to light that comes directly from a tunable laser and by locking the tunable laser wavelength to that of the microtoroid resonance, researchers can sense ultra-low concentrations of the targets.

Sensing for drug research

The researchers used G-protein coupled receptors as the sensing compound for their experiments. GPCRs are sometimes referred to as gatekeepers for cells and are the target of 40% of all pharmaceutical drugs. In addition to regulating cell functions, they act as signalers for cells, one of the reasons they are so important for drug research. For the Nature Communications paper, the researchers looked at the kappa-opioid receptor. “When something binds to one of these receptors, it triggers a signaling cascade within the cell,” said Su. “The kappa-opioid receptor is really important for pain, for example. A future potential application for something like this would be pain relief, but without addictive side effects.” Su says because the FLOWER demonstrates record-level sensitivity in picking up concentrations, its potential use in pharmaceutical research could be a game changer. Stephen Liggett, senior vice president for research at the USF’s Morsani College of Medicine, concurs with Su’s assessment of FLOWER’s potential for drug testing. He explained that scientists could potentially find effective drugs they might miss if testing with other methods. “The ultimate goal of medicinal chemistry is to use all our tools to predict what might be a really good activator of a receptor and build that molecule. Zeptomolar sensitivity is just an incredibly low number, and it has not been achieved by any method we know of to date,” he said. “If you come up with a drug that you feel should work at a certain receptor, if it’s not a particularly high affinity, then most of the time you can’t make a drug out of it because the body can’t take huge amounts of a drug.”

An immediate quantum leap

The work is an exciting breakthrough, said Bruce Hay, a professor of biology at Caltech, who studies cellular biology and was not involved with the research. The new method’s label-free high sensitivity makes it immediately useful for advanced drug screening and other research, according to Hay. “This represents a huge leap in our ability to probe the fundamental components and processes that make up biological systems,” he said. Su and colleagues at UCLA won a $650,000 Phase 1, NSF Convergence Accelerator grant last year to continue their investigations. Convergence Accelerator grants are awarded specifically to speed scientific research likely to produce beneficial applications for society. “Dr. Su’s FLOWER sensor offers a quantum leap on peak sensitivity of label-free biosensing,” said Mario Romero-Ortega, the department head of bioengineering. “This technology will allow a deeper understanding of membrane molecular events, enable early diagnostic assays and improve human health.”