One Act of Kindness Leads to Many More for Society of Hispanic Professional Engineers

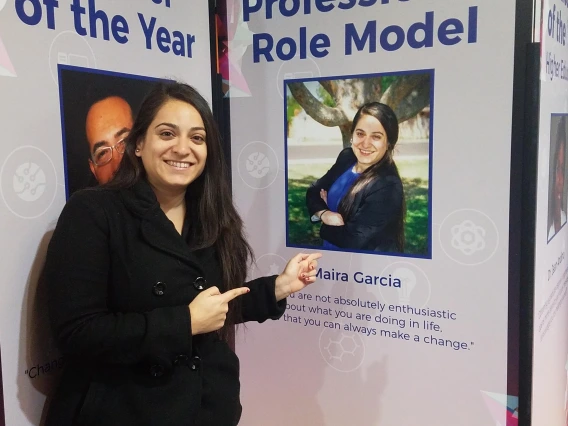

Maira Garcia – a first generation college student and young alum volunteer award winner – pays it forward to fellow SHPErs, many of whom follow in her footsteps.

No description provided

Back in 2010, Maira Garcia was a first-generation college student who didn’t know what to expect from college. But when the AIMS scholar toured campuses, the University of Arizona touched her heart: It looked like a campus out of a movie, she said.

Since her first wide-eyed days on campus, Garcia has graduated with a bachelor’s degree in aerospace engineering, landed a full-time job at Honeywell and started a fundraiser for students in the UA Society of Hispanic Professional Engineers (SHPE). Most recently, she was selected as the 2021 College of Engineering Outstanding Young Alumni Volunteer.

I went for the friendship aspect, but I stayed because they did a lot of professional development and outreach. I realized that if I stayed in SHPE, I was going to become a better engineer.”

Finding Her Campus Familia

Once she started college, Garcia dove into campus life, joining groups like the Society of Women Engineers, American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics, and Advocates Coming Together. She was also a resident assistant, teaching assistant, Engineering Ambassador, and undergraduate researcher in associate professor Jesse Little’s Laboratory.

When she joined SHPE, college life got even better.

“Right when I got to my first meeting, I felt like I was home with my family,” she said. “I went for the friendship aspect, but I stayed because they did a lot of professional development and outreach. I realized that if I stayed in SHPE, I was going to become a better engineer.”

As Garcia’s senior year arrived, she made a bucket list of things she wanted to do before graduation. One of the activities on her list was to attend the national SHPE conference – the largest gathering of Hispanics in STEM in the country. Over 150 companies looking for interns and full-time employees attend. Garcia had always wanted to go, and SHPE-sponsored fundraisers, including a carwash, helped pay her way.

“It really changed my life,” she said. “There were so many people like me. I saw a lot of companies actively recruiting students.”

Garcia had already done two internships at Honeywell and had a secured a full-time job offer for after graduation by the time she attended the conference. But attending helped her build her professional network and skills in ways that set her up for future success. Once she was working, she decided to pay for a SHPE student to attend a conference. She also set up a fund for others to contribute and has since organized a team of fellow engineering alumni to run the fundraiser: Azahel Cordova Arvizu, Jaime Goytia, Fernando Lopez and Juan Sandoval.

“I didn’t want the reason other students couldn’t attend to be a lack of funding,” she said.

SHPErs Come Together

Garcia and four fellow SHPE alumni – Steven Carrillo, Lucio Cota, Jose Estrada and Mario Valdez – raised $1,250 In 2015 and sent five students to the convention, including Erasmo Quijada, who won the Nissan Design Competition at the conference.

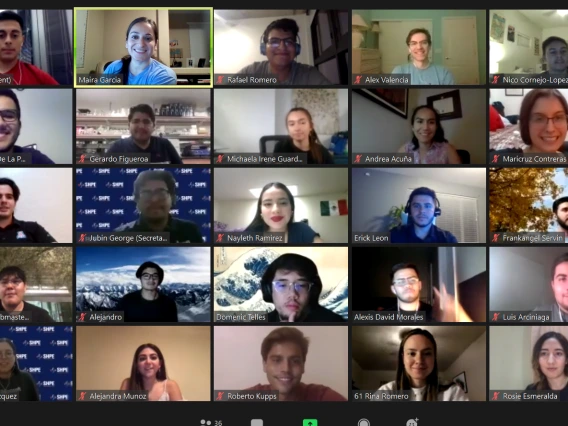

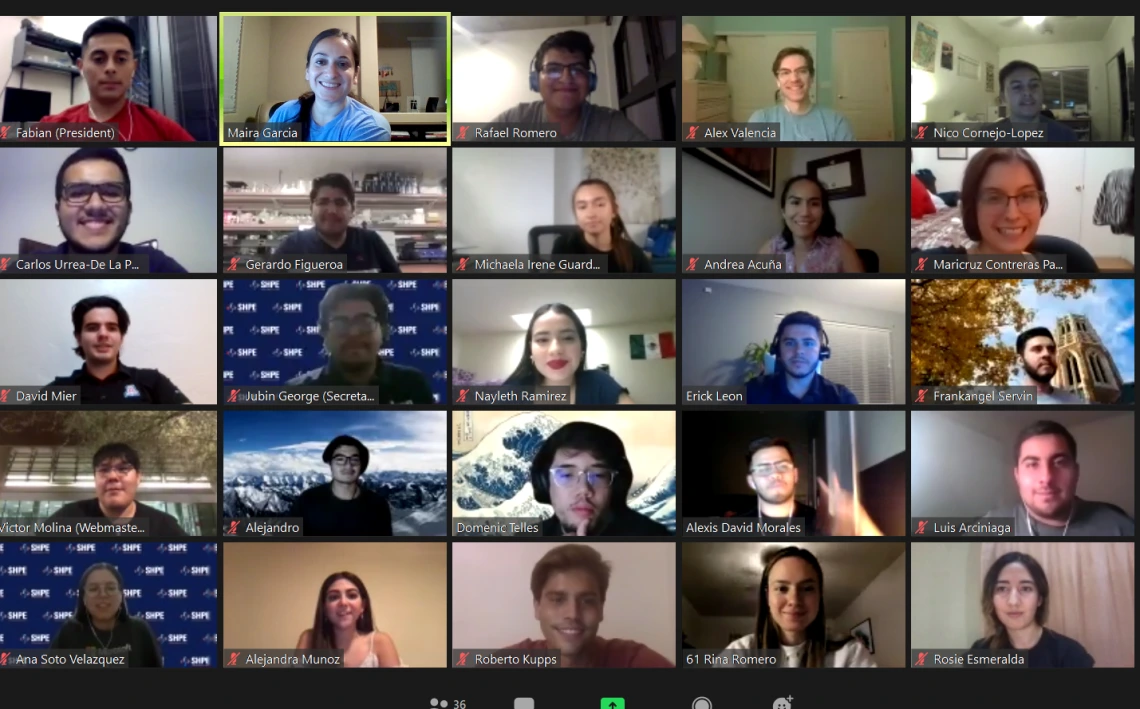

The fundraising team was unsure the conference would happen last year during the pandemic. But even with a late start, they raised $6,400 from 44 donors, more than ever before. The funds sent 16 students to the virtual SHPE conference and provided thousands of dollars in COVID-19 relief scholarships.

Most of the people donating are recent graduates, including Quijada, who now works as a research engineer at Honda.

“I decided to pay it forward and will forever do so,” he said. “Because I would not be where I am today if it weren’t for the great opportunities I had access to through SHPE.”

Nayleth Ramirez, who received the scholarship in 2017, 2018 and 2019, shared the sentiment. When she attended the conference during her sophomore year, she set up two interviews and landed a summer internship at Raytheon Technologies. She interned for the company for three summers and starts a full-time position in September.

“I probably wouldn’t have gone to the conference if I hadn’t won that scholarship because I’m a first-generation student. Sometimes money can be hard when you’re trying to pay for the bare minimum of school essentials,” she said. “But attending really opened my opportunities. Now that I’m an alum, I definitely want to help support SHPE for the rest of my life.”

Continuing the Bucket List

Garcia loves her job at Honeywell and especially appreciates that the company has a presence at the conferences for SHPE, the Society of Women Engineers and the National Society for Black Engineers.

She has started a post-graduation bucket list and completed touring the student-run UA San Xavier Underground Mining Laboratory, attending a UA football game in the College of Engineering VIP suite and giving a keynote speech. She crossed off the keynote speech when she spoke at the UA SHPE’s annual awards banquet in 2016. In 2017, she received the national SHPE Technical Achievement Recognition Professional Role Model Award.

“No matter how much I do, no matter how many talks I give, or how many students I mentor, it will never be enough to repay SHPE,” she wrote in her acceptance speech. “As my mom likes to say, ‘el que siembra en abundancia, en abundancia cosechará,’ which translates to, ‘He who sows in abundance, in abundance he will reap.’ This is the way I have always seen my involvement with SHPE.”

Garcia documents her bucket list adventures in a blog, Enthusiastic About Life. And, she is raising funds to send students to the 2021 SHPE Conference. The fundraiser is open until Sept. 27.