A Tiny Circular Racetrack for Light Can Rapidly Detect Single Molecules

Biomedical engineering and optical sciences professor Judith Su writes about her supersensitive sensor technology for The Conversation U.S.

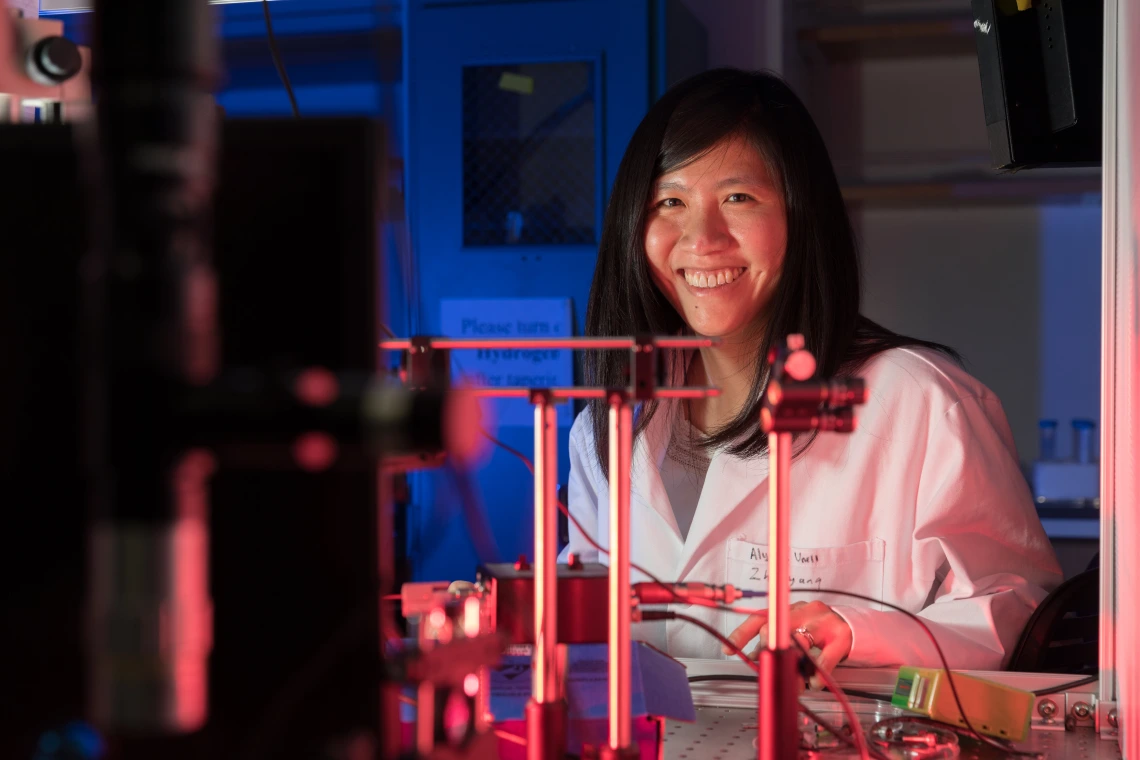

No description provided

My Little Sensor Lab at the University of Arizona develops ultrasensitive optical sensors for medical diagnostics, medical prognostics, environmental monitoring and basic science research. Our sensor technology identifies substances by shining light on samples and measuring the index of refraction, or how much light is slowed down when it passes through a material, which is different from one substance to another – say, water and a DNA molecule.

Our technology lets us detect extremely low concentrations of molecules down to one in a million trillion molecules, and can give results in under 30 seconds.

Ordinarily, index of refraction is too subtle to detect in a single molecule, but using a technology we developed, we can pass light through a sample thousands of times, which amplifies the change. This makes our sensor among the most sensitive in existence.

The device includes a tiny ring that light races around – 240,000 times in 40 nanoseconds, or billionths of a second. A liquid sample surrounds the sensor. Some of the light extends outside of the ring, where it interacts with the sample thousands of times.

Unlike other very sensitive detection methods, ours is label-free, meaning that we don’t have to add any radioactive tags or fluorescent labels to identify what we are trying to detect. This means we don’t have to process our samples as much.

Because our sensor is so sensitive, we require only small amounts of a substance, which is useful both for reducing costs and in cases where reagents are difficult to obtain.

Why it Matters

Some diseases, like cancer, can progress silently, avoiding detection until it’s too late. An ultrasensitive sensor could detect a disease before symptoms appear, letting health care providers treat the disease early, when it’s still curable. The sensor could also be used in a COVID-19 breath test.

Having a rapid and sensitive sensor can also enable monitoring of disease progression and can quantify the effect of different treatments. Our lab, for example, currently works on detecting low concentrations of biomolecules that indicate Alzheimer’s disease or cancer in blood, urine and saliva samples.