Satellite Brightness Threatens Ground-Based Astronomy, Research Shows

AME doctoral student contributes to international research published in Nature.

Starlink satellites, photographed soon after launch, pass overhead near Carson National Forest in New Mexico.

Tanner Campbell, an aerospace and mechanical engineering Ph.D. candidate, is part of an international study confirming that deployed satellites like those that provide broadband internet and mobile phone service are as bright as the brightest stars seen by the unaided eye.

The finding could pose challenges to astronomy as nations and companies launch more and more satellite megaconstellations – large networks of bright satellites – into space. The research was published online today in the journal Nature.

"The proliferation of satellite megaconstellations will have a profound impact on ground-based astronomy. Sunlight reflected by these satellites will leave trails on the images taken by existing and upcoming ground-based surveys such as the Vera C. Rubin Observatory in Chile, making it challenging to do astronomical research," said Vishnu Reddy, professor of planetary sciences at the university's Lunar and Planetary Laboratory and director of the Space4 Center, who is one of the authors of the Nature study.

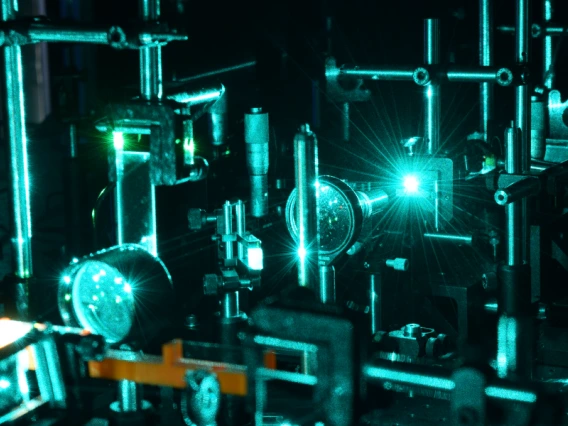

As part of the international effort and in partnership with Starizona, a Tucson-based small business, Reddy, Campbell, and another graduate student built a small ground-based sensor with a camera lens that accurately measured the brightness of the BlueWalker 3 satellite. The satellite, a prototype for the company's BlueBird satellite megaconstellation, had unfurled the largest telecommunications array, spanning 693 square feet.

Astronomers use a scale to measure the brightness of stars in the night sky. The brightness of the stars we can see with an unaided eye ranges from minus 1 at the brightest to 6 at the faintest. Sirius, the brightest star, is minus 1. Planets like Venus can sometimes be brighter – closer to minus 4. Reddy and his team measured BlueWalker 3 at visual magnitude 0.4 – closer to the brightest stars seen in the night sky.

"We realized that measuring the brightness of really bright objects is very challenging, as the light from them can overwhelm the camera," said Campbell. He and LPL graduate student Adam Battle developed the software for analyzing the data.

"Megaconstellations are here to stay, and we have to find a way to mitigate their impacts on ground-based astronomy," said Battle, who was also part of a previous UA study focused on measuring the impact of SpaceX's Starlink megaconstellation. "We currently have more than 4,000 Starlinks and more are being launched every month."