As Reflective Satellites Fill the Skies, UA Students Make Sure Astronomers Can Adapt

University of Arizona engineering students have completed the first comprehensive brightness study to characterize mega-constellation satellites cluttering the skies.

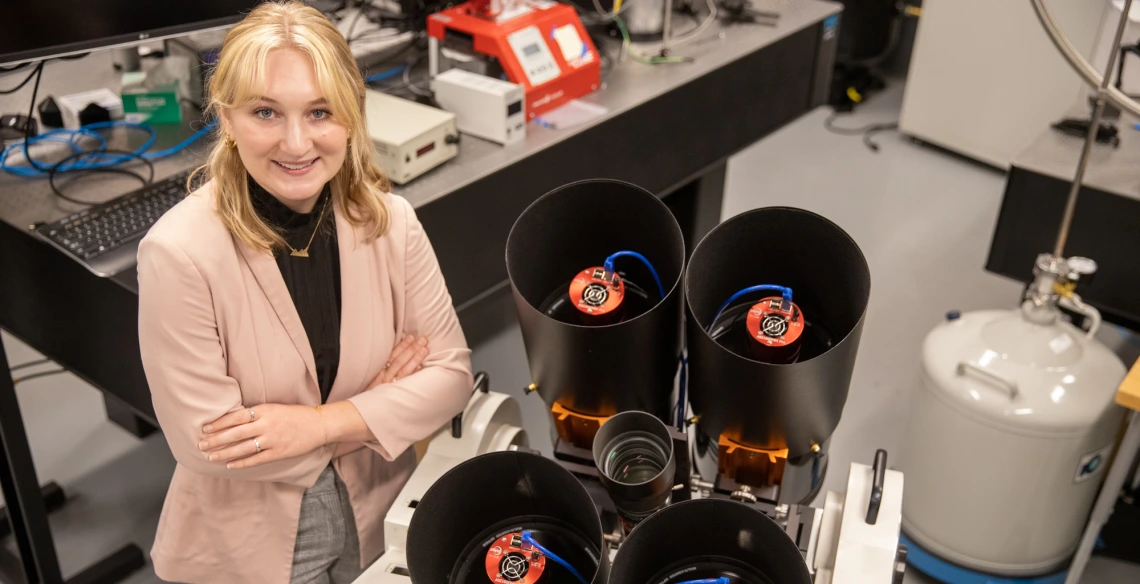

Grace Halferty, a senior graduating this summer with a bachelor's degree in aerospace and mechanical engineering and the paper's lead author, with the instrument researchers built to measure the brightness and position of SpaceX Starlink satellites. (Photo: Kyle Mittan / University Communications)

As satellites crawl across the sky, they reflect light from the sun back down to Earth, especially during the first few hours after sunset and the first few hours before sunrise. As more companies launch networks of satellites into low-Earth orbit, a clear view of the night sky is becoming rarer. Astronomers, in particular, are trying to find ways to adapt.

With that in mind, a team of University of Arizona students and faculty completed a comprehensive study to track and characterize the brightness of satellites, using a ground-based sensor they developed to measure satellites' brightness, speed and paths through the sky. Their work could be helpful for astronomers, who, if notified of incoming bright satellites, could close the shutters of their telescope-mounted cameras to prevent light trails from tainting their long-exposure astronomical images.

The research team was led by professor of planetary sciences Vishnu Reddy, who also co-leads – with study co-author and professor of systems and industrial engineering Roberto Furfaro – the university's Space Domain Awareness lab, which tracks and characterizes all kinds of objects orbiting Earth and the moon.

Grace Halferty, a senior graduating this summer with a bachelor's degree in aerospace and mechanical engineering, is the lead author of the study, which is published in Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. The study details how the team created a satellite tracking device to measure the brightness and position of SpaceX Starlink satellites and compared those observations to government satellite tracking data from the Space Track Catalog database.

"Until now, most photometric – or brightness – observations that were available were done by naked eye," Halferty said. "This is one of the first comprehensive photometric studies out there to go through peer review. The satellites are challenging to track with traditional astronomical telescopes, because they are so bright and fast-moving, so we built what's basically a small sensor with a camera lens ourselves because there was nothing off the shelf available."

Aerospace and mechanical engineering research assistant Tanner Campbell was also involved in the study.