Daughter of Two SIE Pioneers Comes Full Circle

With a father who spent 33 years as a University of Arizona professor and a mother who was the first woman to earn a UArizona PhD in her field, Jane Bambauer never expected she’d end up teaching on the campus where she spent her childhood.

April, Diana, Sid and Jane Yakowitz (now Jane Bambauer) dropping Jane off at Yale for college in 1998.

As the daughter of two engineering PhDs, Jane Bambauer had a STEM-centered childhood. Her father, Sidney (Sid) Yakowitz, had her practice math problems on Saturday mornings before going to play with friends. Her mother, Diana, would make biology and chemistry textbooks for Bambauer’s Barbies, to encourage her to think about a career in science. Bambauer spent a lot of time on the University of Arizona campus, where Sid was a professor and Diana was a student.

“The whole campus, but especially the engineering department, felt like a home away from home,” she said. “I was definitely a ‘fac brat.’”

Bambauer did go on to study mathematics at Yale. But then she decided she wanted to do something different from her PhD parents – she earned a Yale law degree. She didn’t realize that it would eventually lead her right back to the campus where she grew up. Her siblings also have UA connections, with her sister April Yakowitz earning a BA in art in 1984, sister T. Karen Wesley earning a BA in psychology in 1989, and brother Joel Yakowitz studying theater.

An SIE Power Couple

Diana and Sid met in 1976 and were engaged just a few months later. He had been a professor in the Department of Systems and Industrial Engineering at UArizona for 10 years, and she was working in circuit and graphic arts photography. When they got married – bringing together his two children and her one – one of the first things they discussed was that Diana wanted to go back to school. She wanted to study something she couldn’t easily teach herself, and so decided to major in physics.

Diana took just one semester off when Bambauer was born in 1980, then enrolled in summer classes to make up for what she’d missed, completing her BS in 1982.

“In some of my lab classes, I would get approached by people who thought I did really good lab work, and would say, ‘You know, we could really use future lab assistants,’” she said. “I was too busy to do that, between the kids’ piano lessons, violin lessons, and doctor’s appointments.”

Considering her strengths in mathematics and the rise of computers, she decided to do her graduate work in systems and industrial engineering, with a specialty in mathematical programming.

“SIE made sense,” she said. “I realized, from there, any field was open. People with degrees from the SIE department end up working for a ton of different industries.”

She earned her MS in systems engineering in 1983, while also working and co-authoring papers with Professor Henry Hill's solar observations team in the Physics Department. After a pause in her graduate studies, including some time working for Hughes Aircraft as a systems engineer, she decided to complete her PhD.

Diana was the first woman to earn a doctorate from the SIE Department, in 1991. She went on to work for the Agricultural Research Service, the research branch of U.S. Department of Agriculture. There, she produced more than 40 papers and conducted work that inspired two international conferences – one in Hawaii, which she co-organized, and one in Australia. She also worked as an adjunct professor in the Agricultural and Biosystems Engineering Department, where she advised several PhD students.

Sid, who spent 33 years in the department, also had a successful career that included cofounding and directing the university’s Algorithmic Laboratory, writing four books and 97 academic papers, and supervising PhD theses for students in multiple departments. He made major contributions to areas including numerical analysis, adaptive control, machine learning, and pattern recognition – including forecasting flood, rainfall, and reservoir lifetimes, as well as the spread of epidemics such as AIDS. His collaboration with international experts, including former students, produced grants, papers, and lifelong friendships.

In honor of his contributions, Hawthorne House planetary science residents named an asteroid after him: 14149 Yakowitz. Sid retired in May 1999, just a few months before he passed away.

Carrying on an Arizona STEM Legacy

Bambauer was in college when her father died. Partly to honor him, she took a few applied math courses she knew he would have appreciated, rather than the theoretical math she preferred. Then, in law school, she took an empirical law and economics course that changed her life.

“The goal is to see whether laws do what we intend for them to do,” she said. “That just really helped me marry my math and law backgrounds. And so I practiced law for a little bit in Los Angeles, but pretty quickly realized I have the soul of an academic.”

When she decided she wanted to be a law professor, she knew she needed to keep her options open to secure such a competitive position.

“I was prepared to move anywhere in the country to pursue my dream, and it just so happened that the University of Arizona really needed what I had to offer in terms of teaching,” she said. “I cannot tell you how fortunate I feel.”

Bambauer is interested in the ethics and legal restrictions on how data is used, and much of her research focuses on topics like privacy law and free speech. But she’s particularly drawn to problems related to emerging technologies, and how to create legislation related to the tech’s potential impact.

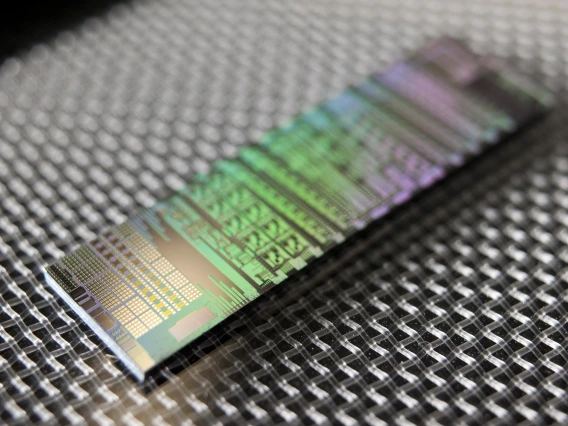

That’s how she became involved with the Center for Quantum Networks, a National Science Foundation Engineering Research Center led by the James C. Wyant College of Optical Sciences. Also featuring lead researchers from the Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering, the center aims to lay the foundations for a socially responsible quantum internet.

As the co-deputy director and Thrust 4 co-lead of the center, Bambauer’s main role is to research how society will change in response to new quantum communication technologies. Then, she’ll use her expertise to help society and the regulatory landscape prepare accordingly. She’ll also play a role in explaining quantum communication technology to the public and investors.

“Because of my background in doing data driven research – and probably because of my parents – I’m able to communicate in that technical language,” Bambauer said. “I think most social scientists and law professors, or others who are drawn to this topic, are drawn to it because there’s a sense of foreboding or threat. But I’m not scared of new technologies.”