Charting a Pathway to Leadership

Kathie Melde, associate dean of faculty affairs and inclusion, writes about her perspectives on leadership and growth for IEEE Antennas and Propagation.

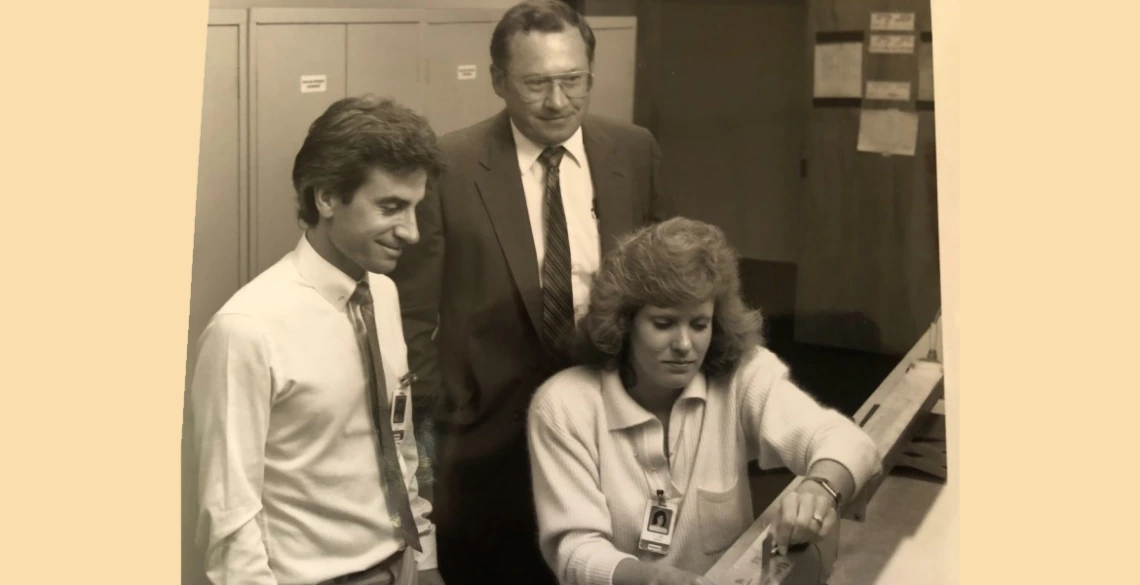

Kathie Melde with two of her supervisors from Hughes Electronics testing a waveguide phase shifter in 1985.

My path to leadership has been bolstered by the experience and confidence garnered by chairing smaller committees and groups through my workplaces (in industry and in academia) and through hands-on involvement in many various organizations, such as the IEEE Antennas and Propagation (AP-S) Society. Leadership was not on my radar when I first started my career, and I turned down many opportunities. It’s okay to say, “no, not now.” I have been selective, and I understand the impact of timing.

The path started by increasingly taking on new roles: lead instructor for a course, faculty advisor to students, lead engineer on a design project, principal investigator on a larger proposal team (generally five people or more), chairing an IEEE/AP-S committee, and others. On this journey, I gained special access to different aspects of organizations and worked on culturally diverse teams. With each rung on the career ladder, I gained greater access to how different people work and was, in essence, handed “the keys to the car” to drive the success of the project or organization.

Reflections on Effective Leadership

During my career journey, the following key lessons stand out:

-

Identify your strengths: You bring your uniqueness to the decision table. Effective teams need thinkers with various strengths. Strengths Finder 2.0 is my favorite resource because it identifies your unique top strengths and guides you on how to build a team to fill in gaps with people with other strengths. My top strengths? Context (i.e., I look back to understand the present), relator (I enjoy turning strangers into friends), individualism (I identify unique qualities in team members), learner, and responsibility. Finding my strengths has led to less frustration and helps me understand that we all have a different lens to the world. It is fun to try to guess who has particular strengths based on how they interact with the group.

-

Identify your blind spots: Find teammates who fill in these gaps. We all have blind spots. They come from our upbringing and personal experiences. Decision making for a diverse population involves decisions that affect a wide net of people and circumstances. Filling in your blind spots early avoids having to revise decisions down the line.

-

Master crucial conversations: You will have many high stakes (i.e., stressful) conversations and learning how to successfully have difficult discussions is imperative. Difficult conversations range from pointing out a colleague’s mistake, standing up to an adversarial supervisor, terminating an employee, or letting someone know they did not receive a much-coveted award. Mastering crucial conversations will provide the tools needed to manage the tension you may feel and to focus on collective problem solving. I have found that in many cases, your colleague or perceived “adversary” is relieved to get through the crucial conversation just as much as you are and you actually gain more trust.

-

Listen to quiet and talkative people equally: Extroverts have no problem controlling discussions. The quiet people often have excellent ideas to contribute but are just waiting their turn (this could be cultural or just someone’s nature). Ask them what they think, take a moment, and then listen to a new set of ideas. This takes practice and a few pauses, but the results can be a game changer.

-

Establish your internal guiding principles: Greater opportunities mean new situations. Leaders often wield power: the power of information, knowledge, hearing from others, and decision making. Many people will be lobbying for you to support their initiatives. Perhaps your superiors will ask you to sign on to something that you are just not okay with. This can be tricky to navigate, and you may be on your own because you are privy to sensitive information. This is when establishing a few internal guiding principles will help. The following are a few of my guiding principles:

-

Sleep on big decisions: Give your subconscious brain time to work on solutions and options. The morning often provides a fresh approach.

-

Bring parties together to discuss difficult matters: Start with individual discussions to vet out the main concerns, but bring people together to honestly discuss all sides of a matter whether it be by phone or Zoom calls or in person.

-

Avoid urgency if possible: Urgency often leads to poor decisions that take a lot of time to fix on the other side.

-

Avoid picking a side until you have more facts (or avoid picking at all): When someone first presents a problem to you, you are only hearing one side. There is always much more involved.

-

-

Use a “ladder” to approach large tasks: When there is much to do with big projects, it can be overwhelming and stressful. Consider breaking down large projects into parts that you can complete and climb just as you would climb rungs on a ladder. I developed this approach to my work after training to run half marathons. Half-marathon training requires a few 20K runs—a daunting thought. My approach is to think of four consecutive mini-5K runs. This way I can celebrate and track my progress on the road to completion.

-

Embrace a growth mindset: Success relies on adapting to change. Students often have a growth mindset because of where they are in their career progression. Seasoned and mature researchers and faculty do not necessarily have this mindset. I spend considerable time working with people who still wish for the “good old days,” even if those days were decades ago.

-

Kindness counts a lot: This also could be written as, “You get more bees with honey than with vinegar.” Humans prefer happiness over pain. If you build in reward structures when people interact with you, you will have more people on your side seeking your counsel, and they will be generally thankful for your help. Often, this need only be a good listener. For me, kindness and openness also means taking the time to correctly pronounce new names in new languages. It’s my small way of letting someone know he or she is important and valued.

The Challenges Women Face Along the Path

This applies to any minoritized population in large groups. Throughout my entire career, there has always been the drive to increase the participation of underrepresented groups in engineering. Although we have made some progress, we (as humankind) still have a long way to go. Progress has been very slow, but we keep trying and we have new tools to measure and engage others. My goal is to provide some lessons that are new to you.

-

Yes, “prove it again” exists and will for some time. This is prevalent in younger women when they make a career change and also when more senior women step into leadership roles. It still surprises me that some engineers and innovators are uncomfortable with changes in organizations and human workplaces. The good news about becoming older is that you get a bit more used to it and develop more ways to either shrug it off or meet it head on. I even enjoy using my “Mom tone” when challenged, although I rarely need to use it anymore.

-

You cannot be too emotional, yet you cannot be too complacent. Many in the workplace are uncomfortable with emotion. Emotion to me is just a natural expression of feelings, but many are not used to it. Practice trying to remain in a calm state, and learn the methods of crucial conversation to remain calm. On the other hand, don’t get too complacent that you miss opportunities. Find the middle ground that helps drive you to personal success and to get the results you need from others.

-

You will be a role model, whether you think yourself of one or not. As a part of a minority population in a large group, others in the group are trying to understand how to work with you. They are learning from you. Women know we are not all the same and have different personalities and strengths. As a role model, there is different standard: how you dress and how you speak to get the results you achieve. As you grow into a leadership role, the role model part of you can be a great strength and a powerful tool to get things done.

-

You will also be surprised about how many little things still have not been solved for women as a whole to be successful in their careers. The COVID-19 pandemic has uncovered the great imbalances with many roles women take on to maintain work/life balance. There is still much to be done. Sometimes there is a vaguely written policy and sometimes there is not. It can be helpful to have some solutions available to work out for your situation. The supportive network discussed in this article is helpful to identify these.